I

La Libération

“A party with plenty to drink the day after the Liberation; far left, Eddie; among the guests you can recognise Georges Guétary, Suzy Solidor, Bernard Peiffer and Charles Aznavour’s partner Pierre Roche.”

II

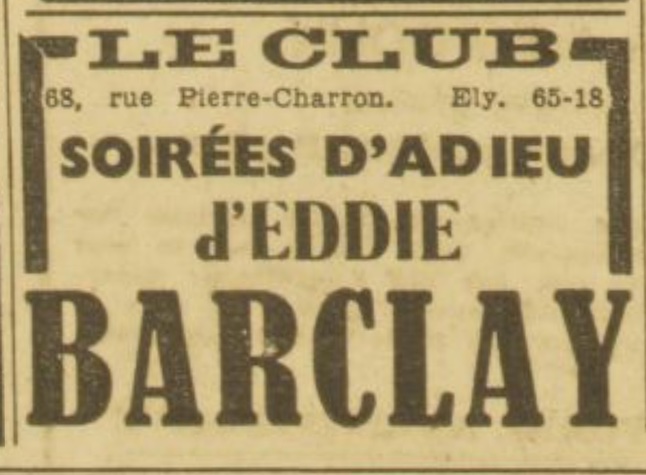

Le Club

And Charles Delaunay again:

« Et le destin, hasard, bref ce que l’on voudra. Charles Delaunay qui me téléphone un matin pour me dire : ‹ Voilà, j’ai un ami qui cherche un pianiste de bar, tu ferais sûrement bien l’affaire, va le voir de ma part, 46, [68] rue Pierre Charron [Paris VIII][[•]] ›. Le monsieur possédait un club qui s’appelait Le Club justement. Le monsieur, qui est devenu mon patron, était Pierre-Louis Guérin,[[•]] et nous nous sommes si bien entendus qu’il n’a plus cessé de me considérer autrement que comme son fils ».[•]

“And it was fate, a stroke of luck, call it what you like. Charles Delaunay rang me one morning and said: 'Look, a friend of mine is trying to find a bar pianist, you’re bound to do the trick. Go and see him, tell him I sent you, it’s 46, [68] rue Pierre Charron [Paris VIII] [•] .’ And this gentleman had a club, it was actually named ‘Le Club.’ The man became my boss, and his name was Pierre-Louis Guérin.[[•]] And we got on so well that ever after he considered me like his own son.”

Eddie Barclay was billed at “Le Club” from October 1944 to October 1945, a decisive year in which he met Allan Morrison and Nicole Vandenbussche.

« Chez Pierre-Louis Guérin, juste après la guerre (pendant la guerre on n’avait pas le droit de danser), j’ai monté un petit orchestre, rue Pierre-Charon. Il y avait Stéphane Grappelli qui venait jouer, plus un trombone de l’orchestre de Glenn Miller [prob. Nat Peck], Boris Vian et une section rythmique qui aimait et jouait cette merveilleuse musique : le jazz. C’était donc l’orchestre d’Eddie Barclay. Tous les soirs au bar, à la même heure, à la même place, il y avait un Noir américain, un militaire qui adorait lui aussi le jazz… Allan Morrison buvait des coups avec moi, on discutait musique pendant des heures, ensuite il venait à la maison écouter mes disques. J’en possédais d’assez rares, ceux qui venaient tout droit de Suisse, et des ‹ V discs › comme on les appelait alors, ceux qu’on distribuait aux militaires américains basés en France et qui s’arrachaient. Morrison les connaissait, bien sûr, mais ça nous créait des liens d’entendre ensemble Benny Goodman, Count Basie, Duke Ellington, Glenn Miller, etc. Morrison démobilisé est reparti pour l’Amérique. Nous nous écrivions souvent… »[•]

“At Pierre-Louis Guérin’s home, just after the war (during the war we weren’t allowed to dance), I put together a small band (at the place in) rue Pierre-Charon. There was Stéphane Grappelli who came to play, plus a trombone from Glenn Miller’s orchestra [prob. Nat Peck], Boris Vian, and a rhythm section that loved and played this wonderful music: jazz. So that was Eddie Barclay's orchestra. Every evening at the bar, same time, same place, there used to be a black American, a soldier who also loved jazz…. Allan Morrison would drink shots with me, we we’d talk about for hours, then he would come over to the house to listen to my records. I had quite a few rare ones, those that came straight from Switzerland, and 'V discs' as they were called then, the ones distributed to American soldiers stationed in France, and they were always snapped up. Morrison had heard them of course, but that created a bond between us, listening together to Benny Goodman, Count Basie, Duke Ellington, Glenn Miller etc. When Morrison was demobbed he went back to America. We used to write to each other often…. “

Allan Morrison[•] was a journalist, the first black war correspondent for Stars and Stripes, the official U.S. military newspaper. He entered Paris with the Liberation army, and he was cultivated, a militant and a loyal Eddie Barclay friend. To know more about Allan Morrison [click here].

III

Blue Star

On Thursday 1st of February 1945

at Studio Technisonor, 50 rue François 1er, Paris VIII,[•] the first recording session took place for Eddie Barclay and His Orchestra.[•] Seven sessions would follow, with Jacques Diéval, Arthur Briggs, and our friends Jerry Mengo and Christian Bellest (the last session on 21 April 1945 with Charlie Lewis)[•]

before the commercial registration on Thursday 7 February 1946 under the N° 838912: “Ruault, Edouard known as Eddie, edition and publication of records, 54 rue Pergolèse, Paris 16e.”[•]

The Blue Star label was born!

Monday, July 9, 1945 Eddie Barclay marries Michèle Barraud,[•] a wholesaler’s daughter. They have met a few years ago (see “Michèle Blues,” Swing SW 156, January 14, 1943.)

« Le lundi 9 juillet 1945, Edouard Ruault, commerçant, né à Paris douzième arrondissement, le vingt-six-janvier mille-neuf-cent-vingt et un, vingt-quatre ans, domicilié à Paris 54, rue Pergolèse… d’une part / et Michèle Françoise Barraud, sans profession, née à Paris quatorzième arrondissement le quinze mai mille-neuf-cent-vingt et un, domiciliée à Paris 190, avenue du Maine d’autre part ont déclaré l’un après l’autre vouloir se prendre pour époux… Mairie du quatorzième arrondissement de Paris. »[•]

“On Monday, July 9, 1945, Edouard Ruault, tradesman, born in Paris, twelfth arrondissement, on the twenty-sixth of January nineteen hundred and twenty-one, twenty-four years old, domiciled in Paris, 54, rue Pergolèse… on the one hand, and Michèle Françoise Barraud, without profession, born in Paris, fourteenth arrondissement, on the fifteenth of May nineteen hundred and twenty-one, domiciled in Paris, 190 avenue du Maine, on the other hand, did declare one after the other to take each other for spouse… Town Hall of the fourteenth arrondissement of Paris.”

At the close of World War II, the state of jazz in France as seen by Allan Morrison in Stars and Stripes:

“French Jazz,” Zazou Is All Hepped-Up About It, but the Artist Questions Its Vitality. Paris. French jazz—that alien hybrid, whose growth was hindered by war and the German occupation, is making a strong effort to regain a healthy footing. Commercially times are good. The nightclubs and cabarets reopened their doors to their own jazz-starved civilians and to the thousands of pleasure-bent, swing-loving, Americans, who poured into the country. But artistically the situation is not too encouraging. Only the “zazou” (jitterbug) set is enthusiastic about it. Musicians themselves admit sadly that French jazz today lacks vitality and needs an infusion of fresh American talent. Otherwise they fear jazz in France may degenerate into a weak, corny form that bears no resemblance to its Yankee father. Long before the great American jazz renaissance of 1936 there was a large group of enthusiastic jazz lovers in France who considered jazz a form of art and dignified it with an esthetic criticism. These enthusiasts later organized a national jazz appreciation movement—the Hot Club de France—with several thousand members and branches throughout the country. Le jazz hot was their religion and its two chief apostles were aristocratic Hugues Panassié, whose books on jazz have been widely read in America, and frail Charles Delaunay, artist, hot-record researcher, and one of the most devoted jazz lovers in the world. Panassié spends his time at Montauban in the Lot-et-Garonne Department, where he keeps his vast jazz record collection. Delaunay directs the Hot Club from its headquarters—a three-story house on Montmartre’s Rue Chaptal—where he edits the club’s monthly bulletin, organizes jazz concerts and jam sessions, and works on the current edition of his internationally-known Hot Discographie, a classified listing of important jazz records. Occasionally the Hot Club rounds up a group of the top French jazz artists for a “bash” in the 52nd Street tradition. These sessions are held in staid old classical halls like the Salle Pleyel and the Ecole Normale de Musique. Usually they are sell-outs, for the Paris jazz movement is large and loyal. If it’s a representative group, the line-up will look something like this: Pierre Fouad or Armand Molinetti at the drums, Emmanuel Soudieux on bass, Aimé Barelli on trumpet, André Ekyan on alto sax, Alix Combelle on tenor sax, Léo Chauliac at the piano, Hubert Rostaing on clarinet and Django Reinhardt at guitar. Out of these sessions comes probably the only true jazz played in France today. Americans who were jazz connoisseurs at home eagerly seek out the familiar names which took part in the get-togethers and produced the records. These sold in the States under the label which said: “Hot Club of France.” And those who thought jazz was something which was strictly an American product were surprised to find that the condition isn’t localized to a few blocks in the 50s in N.Y., the Village and Harlem. It’s international now and respectable. Fabulous Django Reinhardt is the greatest single institution in the French jazz world. Born of gypsy parents in Belgium, he learned to play the guitar in the atmosphere of a gypsy caravan in the Paris suburbs. His phenomenal technique is the more amazing because of a deformity which deprives him of the use of two fingers on his left hand. Temperamental, moody, superstitious and vain, Django is probably the only French musician to charm and influence American jazzmen. He has been called a genius of modern music, though he cannot read a note. Django, Aimé Barelli, André Ekyan and Alix Combelle are the four most successful and important French jazzmen. Each fronts a combination of his own. Django and Ekyan head small jam groups that play with great freedom, while Barelli and Combelle lead larger units that feature written arrangements. Combelle is the best-known bandleader in the country and the highest paid. French musicians are eager for American jazzmen with whom they can jam. Many think that upon this association rests the future of French jazz. Many French jazz musicians say that they will visit America when the travel restrictions are lifted to study the American swing technique. America alone, they contend, can nourish the withering plant that is French jazz. Husky, sardonic Ekyan, now playing, at Schubert's in Montparnasse, is deeply pessimistic about the immediate future of jazz in France. Says he: “Jazz will never be fully accepted or understood in France. Around 1938 it started to be fashionable to like jazz, almost a vogue you might say. But it is foreign music and will always be so. At best, we French musicians will play it with an accent. Our problem is to reduce the degree of accent. Perhaps we will never remove it entirely, for it is American music first and always, but we can seek that end.” Allan Morrison, Stars and Stripes Staff Writer”

[•]

Chicago Defender journalist Ben Burns,[•] later a friend of the Barclays, was his paper’s special envoy in Paris to cover the World Federation of Trade Unions.[•] He reported on his meeting with Allan Morrison, allowing readers to know him better, both as a man and as a professional:

“… my luck in starting a new career at the Defender was climaxed by a choice assignment at the end of the war. Considering the tight-fisted reluctance of its management to dole out expense dollars for out-of-town staff coverage, I was astounded in the fall of 1945 to merit approval for a European assignment: to cover the initial organizing sessions go the World Federation of Trade Unions (WFTU) in Paris. The suggestion for the Defender to report the leftist-nurtured conference in the wake of the wartime Allied unity of Washington and Moscow, I assumed, must have originated with my leftist sponsor, William L. Peterson (a belief reinforced by the jubilant Daily Worker Headline, ‘Defender Send Burns to Paris’[[•]]), and was enthusiastically embraced by editor-in-chief ‘Doc’ Lochard. It was hardly necessary to ask if I would be willing to go to Paris

.…”[[•]] “To me the Old World was a new world, and I fell in love at first sight with the great city. Every moment I could spare from the conference sessions, I stole away to marvel at its wonders, from museums and churches to boulevards and squares. Strolling down the Champs-Élysées one afternoon, I accidentally encountered some black GIs, one of whom was a friend of Charles Collins, my shipboard roommate. He was a staff writer for Stars and Stripes, Allan Morrison, whom I had never met but who was know to me as the past editor of an ill-fated version of Negro [World] Digest [[•]] that had published several issues almost simultaneously with John Johnson’s magazine [[•]] before dying for lack of funds. Drafted into the army, Morrison became one of the very few Negro staffers on the military daily, and I spotted him as a magazine writer whose talents could be a valuable addition to our staff if and when we were able to afford an editorial payroll. Negro Digest had reprinted several of Morison’s pieces from Stars and Stripes, and in our meeting in Paris I Immediately established a rapport with the equable, astute writer, whom I urged to contact me for a job when he was out of service. The soft-spoken but highly articulate Montreal-born Morrison (whose parents were from Jamaica) later came to be a close friend. He was one of the most gifted and conscientious black journalist I have known, a dependable, forthright intellectual who showed great acuity in many articles he later wrote for me as New York bureau chief of Ebony magazine. I often turned to him for guidance and comfort when faced with perplexing editorial decisions, and he could always be depended on for judicious sagacity, especially on sensitive racial issues.”Ben Burns[•]

Eddie Barclay leaving Le Club at the end of October 1945. He had met Nicole.

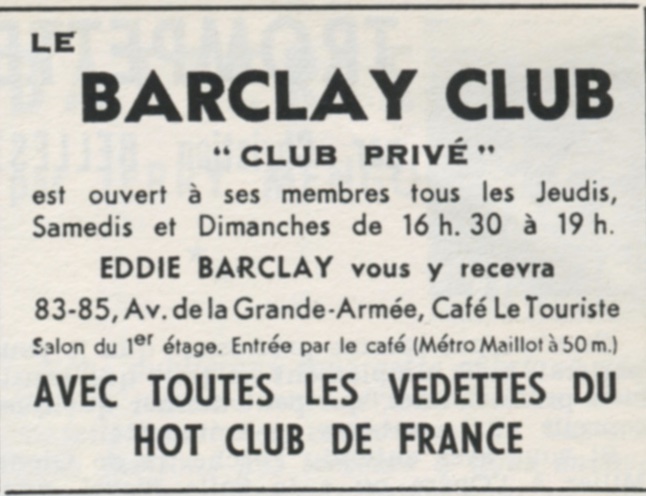

Returning to the world of private clubs, Eddie Barclay developed the name “Le Barclay Club" in November 1945[•]:

« C’est à peu près à cette époque que j’ai lancé les Barclay’s Clubs; des endroits fréquentés surtout par des jeunes, où l’on pouvait boire, écouter de la musique, danser pour une dizaine de francs, somme très modique ».[•]

“It was around this time that I started the ‘Barclay’s Clubs’; places regularly visited by mainly young people and where you could drink, listen to music, dance for about ten francs, a very modest sum.”

On his return to the USA, Allan Morrison started working in Chicago for the editor/publisher John H. Johnson:

“Didja know that Allan Morison, only colored correspondent on Yank and Stars and Stripes, has joined the staff of Ebony and the Negro Digest? His first two pieces will appear in the March first issue of the former.…”[•]

Allan Morrison renewed his acquaintance with his friend Eddie Barclay; in return, the latter replied to him on 26 April 1946:

Cher vieux Morrison, j’ai été vraiment très heureux de recevoir de tes nouvelles. Je me doutais que tu avais beaucoup de choses à faire après une si longue absence, et j’étais sûr que tu m’écrirais bientôt. C’est merveilleux, tu as une [not readable] de deux journaux, c’est beaucoup de travail, mais certainement beaucoup d’argent aussi. Je suis content pour toi. Quant à moi, je m’occupe toujours de ma marque de disques ”Blue Star” d’une part, de mon club d’autre part et je joue aussi un peu, quand j’ai le temps. Tu vois que j’ai aussi beaucoup de travail. Je t’enverrai prochainement les disques de ma marque qui pourraient t’intéresser et surtout le Body and Soul que tu aimais beaucoup [Probably Blue Star BS. 1]. À propos de disque, je désirerais savoir si tu pourrais me faire une séance d’enregistrement (4 ou 6 faces) avec un petit groupe de très bons musiciens (comme Lester Young, Joe Jones etc…) 7 ou 8 musiciens suffisent pour faire de bonnes Jam sessions ou de petits arrangements bien en place. J’aimerais que la totalité de l’orchestre soit formée avec des musiciens noirs. Si tu peux pas avec Lester vois en d’autres. Donne moi aussi une idée de ce que me couterait ces 4 ou 6 matrices. (Paye des musiciens, des arrangements, de l’enregistrement et des matrices prêtes à être expédiées en France). Essaie de me donner une réponse rapide; je voudrais bien être le premier en France à faire paraître de nouveaux disques de noirs américains, enregistrés en Amérique. Je te remercie pour le colis que tu vas m’envoyer, tache d’y joindre quelques disques les meilleurs nouveaux. Tu remercieras aussi ta femme pour le mal qu’elle se donne, à cause de moi. J’oubliais aussi les deux stylos over sharp du dernier modèle, (or 14 carats) si c’est possible. Tu me diras l’argent que je dois pour tout cela et je t’enverrai aussitôt la somme par chèque ou par mandat. Je ne compte malheureusement pas aller en Amérique avant 6 ou 8 mois; trop de travail pour le lancement de mes disques est nécessaire. Mais soit sûr que j’y viendrai et que je m’arrangerai pour te voir. En attendant les bons moments que nous passerons de nouveaux ensemble, reçois de ton vieil ami un vigoureux “shake-hand” et toute sa joie de correspondre le plus souvent possible avec toi. Eddie

Eddie Barclay, 54, rue Pergolèse, Paris XVI.

[écriture manuscrite] Un gros baiser bien amical sur la joue droite, Michèle [Barraud][•]

My dear old Morrison, I was really very happy to have news from you. I guessed you had a lot of things to do after such a long absence, and I was sure you would be writing to me soon. It’s marvellous, you have a [illegible] of two newspapers, that’s a lot of work, but certainly also a lot of money. I’m happy for you. As for me, I’m still busy with my record label ”Blue Star,” and then there’s also my club, and I play a little too, when I have the time. You can see that I have a lot of work too. I’ll be sending you some of my label’s records shortly; you might find them interesting, and especially the ‘Body and Soul’ you liked so much [probably Blue Star BS. 1]. Speaking of records, I’d like to know if you could do a recording session for me (4 or 6 sides) with a small group of very good musicians (like Lester Young, Joe Jones etc…) 7 or 8 musicians are enough to do good jam sessions or some well set-up little arrangements. I would like the whole band to be made up of black musicians. If you can’t with Lester, see with some others. Also, give me some idea of what these 4 or 6 matrices would cost me. (Musicians’ wages, arrangements, the recording, plus matrices ready for shipment to France). Try to give me a quick answer, I would like to be the first in France to release new records by black Americans, recorded in America. Thank you for the package you’re going to send me, try and enclose a few records, the best new ones. Thank your wife also for the trouble she’s taking on my account. I was forgetting, also two Eversharp pencils of the latest model (14 carat gold) if possible. You’ll let me know how much I owe you for all that and I’ll send you the money at once, either a cheque or money-order. Unfortunately I can’t plan to visit before another 6 or 8 months; there’s too much work involved in the release of my records. Best rest assured, I will be coming and I’ll make it possible to see you. Until those good moments that we will be spending together again, receive this vigorous hand-shake from your old friend, and all the joy of corresponding with you the most often possible. Eddie

[handwriting] A very friendly big kiss on the right cheek Michèle [Barraud]

Letter and request unanswered.

Paris, 27 juin 1946. Cher, Morrison, Aucune nouvelle de toi depuis ma dernière lettre, peut-être ne l’as-tu pas reçue, ou peut-être aussi que ta réponse est égarée, c’c'est possible. J’espère que tu vas toujours bien ainsi que ta femme. Est-ce que ton travail est toujours aussi intéressant pour toi? Écris-tu beaucoup d’articles? Dans ma dernière lettre je te demandais si tu pouvais te charger d’une session de disques à enregistrer? Est-ce que tu peux faire cela pour moi? Je t’enverrai de l’argent aussitôt pour payer les frais d’enregistrement. Donne-moi tous les détails à ce sujet. Je viens d’être opéré, je suis encore au lit pour une quinzaine de jours, tout s’est bien passé, on m’a retiré ma vésicule biliaire et mon appendice, je vais bien maintenant. Veux-tu me dire si tu peux m’envoyer un près petit appareil de radio à accus (comme il y avait dans l’armée américaine). Son volume n’est pas plus gros qu’une boîte de trois savons de toilette, vois-tu ce que je veux dire? Tu serais bien gentil de me le joindre dans mon colis avec quelques accus de rechange. Dis-moi aussi à quelle adresse, je dois envoyer l’argent que je te dois pour cela? Je te remercie, et je m’excuse aussi à l’avance, pour tous les dérangements que je te procure. J’espère avoir de tes nouvelles très bientôt, en attendant ta lettre je t’envoie ainsi que Michèle [Barraud] toutes nos amitiés et te serre cordialement la main. Bien à toi, E. Barclay

P.S. Parmi les disques que tu dois m’envoyer, mets moi quelques “Woody Herman”. J’aime beaucoup cet orchestre et je n’ai aucun disque de lui.[•]

Dear Morrison, Haven't heard from you since my last letter, maybe you haven't received it, or maybe your reply was lost, it's possible. I hope you and your wife are still doing well. Is your work still interesting for you? Do you write a lot of articles? In my last letter I asked you if you could take care of a recording session? Can you do this for me? I will send you money immediately to cover recording expenses. Give me all the details about it. I just had surgery, I'm still in bed for a fortnight, everything went well, they removed my gallbladder and my appendix, I'm fine now. Would you like to tell me if you can send me a very small battery-powered radio device (as there was in the American army). Its volume is no bigger than a box of three toilet soaps, do you see what I mean? Would you be kind enough to put it in my parcel with some spare batteries? Also tell me to which address I should send the money I owe you for this? Thank you, and I also apologize in advance for any inconvenience I cause you. I hope to hear from you very soon, while waiting for your letter I send you and Michèle [Barraud] all our regards and cordially shake your hand. Yours, E. Barclay P.S. Among the records you have to send me, put me some “Woody Herman”. I really like this orchestra and I don't have any records from it. (June 27, 1946)

P.S. Among the records you have to send me, put in a few by Woody Herman. I really like this orchestra and I don't have any records by it.

IV

Blue Star New Departure

After a 17-month interruption, back to recording. Monday 9 September 1946, session at Studio Technisonor, 50, rue François 1er, Paris VIII, with Tony Proteau and His Orchestra.[•]

Between June and October 1946, Michèle was no longer "the wife" of Eddie;[•] but Nicole, officially "the new” one. Letters to Allan Morisson were in English. This period can be considered a new departure for the Blue Star label. Eddie Barclay would remember it, and paints a moving portrait of Nicole, filled with gratitude and admiration, in a chapter (3) devoted entirely to her under the title “Blues pour Nicole.”[•]

« Je continuais mon petit boulot de pianiste chez Guérin, et c’est mon copain Georges Dambier[•] qui me l’a présentée: « Elle était… pulpeuse, façon Judy Garland, un genre que j’aime à la folie. Elle était belle… » « Salut, je te présente Nicole, Nicole voilà Eddie Barclay »… nous avons eu le coup de foudre[•] … »

"I was continuing my little job as a pianist at Guérin’s place, and it was my friend George Dambier [•]who introduced me to her: "She was.... luscious, Judy Garland style, a genre that I love madly. She was beautiful….” “Hi, this is Nicole. Nicole, this is Eddie Barclay”…. we fell in love….[•]